In early April, the Horizon staff surveyed 40 students, as well as 18 teachers and faculty, on whether or not they could name all five of the freedoms described by the US Constitution’s First Amendment.

The First Amendment details some of the most fundamental rights given to Americans. It reads as follows: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Responding either in person or through a Google Form, Skyline’s community contributed to a test to see if Skyline would have better statistics of identifying these rights than those presented in Freedom Forum’s Where America Stands 2024 Survey Results. (It is important to note that Freedom Forum’s survey included 820 individuals, which is more than 14 times the Horizon’s survey pool.) Overall, 98% of Skyline respondents could name at least one right, compared to 96% of the general population.

The most commonly remembered right is by far freedom of speech, both according to the Freedom Forum survey and the Horizon’s own. Overall, 92% of Americans can name this right, and about 97% of Skyline participants could—although, all faculty respondents named this right successfully. After speech, religion is the first to come to mind, with 62% of Americans and about 76% of Skyline naming it.

The Skyline poll went off course, however, when freedom of press became the easiest to name after religion. In Freedom Forum’s, freedom of assembly came next highest instead. Skyline could name press about 66% of the time, while Americans in general could only get it 57% of the time. After press was assembly, which marked the first freedom that didn’t get named more frequently in Skyline’s polls. The US in general had a 59% success rate; Skyline had 55%.

The lack of recognition for freedom of petition was even greater. In the Freedom Forum survey, 41% of Americans could name this right, but only 17% of Skyline remembered it. The percentage of people who named petition in the Skyline survey directly correlated with the percentage who could name all five rights, meaning everyone who named four rights (24%) forgot petition specifically.

Other common responses included “to gather” and “to protest,” which were not counted, despite their close relation to freedom of assembly, due to imprecise wording. “Expression” was named a few times as well. This makes sense, as the First Amendment is often summarized as the amendment that protects freedoms of expression. This connection is part of the reason why, when three respondents were specially asked if all five freedoms were equally important, they responded yes. One anonymous teacher said, “You can’t have freedom of religion if you can’t assemble.” Another explained, “They’re all intertwined.”

The same three respondents were asked if they would sign the amendment into law if it was up to them today—unanimously, they said yes, which is a much higher percentage than Freedom Forum’s 58% saying so.

Jeremiah Newlove, a student who named all five freedoms, was one of these respondents. He explained, “I believe these are basic human rights and are used on a regular basis by most people. People fought for these rights, and had I been in power to sign this in, I trust the people to know what they want but also why they want it. People don’t just fight for the right to speech or press for fun.”

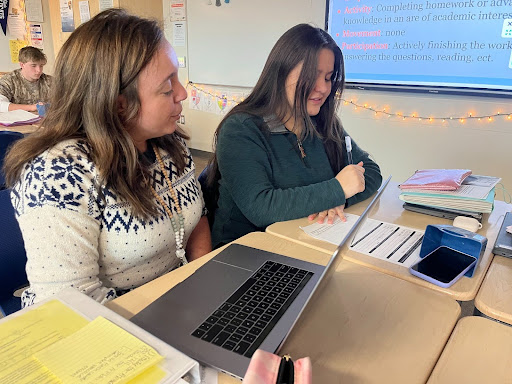

With how many people can’t name all five, it’s also possible that the rights people are fighting for are misunderstood. Being one of only two teachers who named all five rights, US History teacher Heather Green explained that some people don’t understand that their free speech, for one, isn’t absolute. “If you are going to threaten somebody through what you say or […] incite some kind of violence or harm on others, […] using the ‘well, I can say whatever I want, or I can do whatever I want’ isn’t gonna fly,” Green said.

Similarly, assembly is specifically restrained by the amendment to be “peaceable.” One anonymous teacher said, “You can have a little picket and throw your signs up, but if you start blocking roadways and sidewalks and start throwing stuff, then we’ve got problems.”

Misunderstanding freedoms and not being able to name them both limit one’s ability to utilize the amendment, as people can unknowingly let their rights be violated or infringe on the rights of others. How can misinformation or lack of information be rectified, though? Green suggests a school campaign to increase awareness. “Maybe focus a day on each of the freedoms,” Green suggested. “You could do like lunchtime things, […] maybe different activities to get people more aware. I think a lot of it has to do with education and awareness, really.”

Increasing awareness isn’t just important for students, who should review the First Amendment in their Senior year US Government class. After all, 20% of students named all five, but only 11% of faculty did. The fact that so few teachers could get them all, including US History teachers, shocked US History teacher Tim Henry, who found the survey easy. A school campaign would be beneficial to these teachers as much as to the students if it worked to increase awareness.

As Henry says, “All Americans should know their First Amendment rights.”